Your browser is not compatible with this application. Please use the latest version of Google Chrome, Mozilla Firefox, Microsoft Edge or Safari.

The Value Crisis

Recently, I’ve been focused on currents of “Marxists” who are invested in Marx not for analysis but from a lifestyle content perspective, as I covered in my recent Very Important Documentary, Marx For Sale. I’d like to address a trend I’ve seen more of; some within these currents are becoming hostile to Marx’s concept of “overproduction.”

The term is often interpreted literally – “too much production” – and I think this is one of the key reasons. To see it through this lens suggests a straightforward surplus of goods, but Marx’s concept isn’t that. It delves into the systemic contradictions, class dynamics, and cyclical crises inherent in the mechanics of capitalism. Marx’s “overproduction” is not about the amount produced; it’s about value and its realization within a capitalist economy.

Other groups, particularly degrowth advocates, are using the term to promote their own agendas, using the literal lens’s quantitative appearance of “too much” to argue for “less.” However, Marx aimed to convey the qualitative and systemic implications of the inherent contradictions and inevitability within capitalist modes of production.

We can’t just drop the term because it is in Marx’s work. To read and refer to Marx means the words will be seen. However, I would like to propose an alternative way to bring up Marx’s “overproduction” to avoid confusing it with what it isn’t.

So in this entry, I’d like to talk about capitalism’s inevitable “Value Crisis.”

What does Marx mean?

According to Marx, overproduction arises from capitalism’s inherent contradictions and tendencies.

In capitalist systems, production is driven by the pursuit of profit. Capitalists invest in the means of production, such as factories and machinery, and hire workers to produce commodities. However, the goal of production is not simply to meet the needs of society but to generate surplus value, which is the source of profit.

As development occurs under capitalism, production output is often increased. Why? For greed’s sake? To expand profits and grow? One could certainly point out examples where this is the motive, but we must not think through ideals. What is the material interest in place? Over time, new technology and production techniques reduce the labor necessary to make a product and thus decrease the product’s value. This is referred to as “the falling rate of profit” or “the tendency of the rate of profit to fall” (TRPF).

This isn’t a concept that started with Marx; Adam Smith also believed in a variation of it. Marx took the analysis further by incorporating the overall dialectical class struggle and identified it as a result of capitalism’s fundamental flaw: the socialization of production with a private (feudal) appropriation of the product and profit.

(Caleb Maupin has a simple, clear, 7-minute explanation for the TRPF and overproduction that can be viewed here).

The TRPF is a crucial aspect of Marx’s analysis of capitalism. It leads to a higher ratio of constant capital (investments in means of production, which a capitalist can’t simply change on a whim) to variable capital (wages paid to workers, which a capitalist can change on a whim). This ratio is referred to as the organic composition of capital, and it has two important effects on the rate of profit.

Firstly, it leads to decreased profit produced per unit of capital invested. As mentioned a moment ago, investing in machinery and technology tend to reduce the labor necessary to produce something, which decreases its value.

Secondly, this does something that sounds good from a worker’s perspective (but isn’t): a decline in the rate of exploitation of workers. Sounds great, but practically speaking, this means more unemployed or underemployed workers and lower and lower wages (the only element that can be cut away at the capitalist’s whim).

So, capitalists are increasing output to maintain, while the worker – ultimately the consumer – is getting paid less. Even if this were not the case, the worker only takes home a portion of the value created and thus could never buy back the full product of their labor. But this continues to compound. Prices go down, sure, but the worker’s available money also goes down – and at a faster rate!

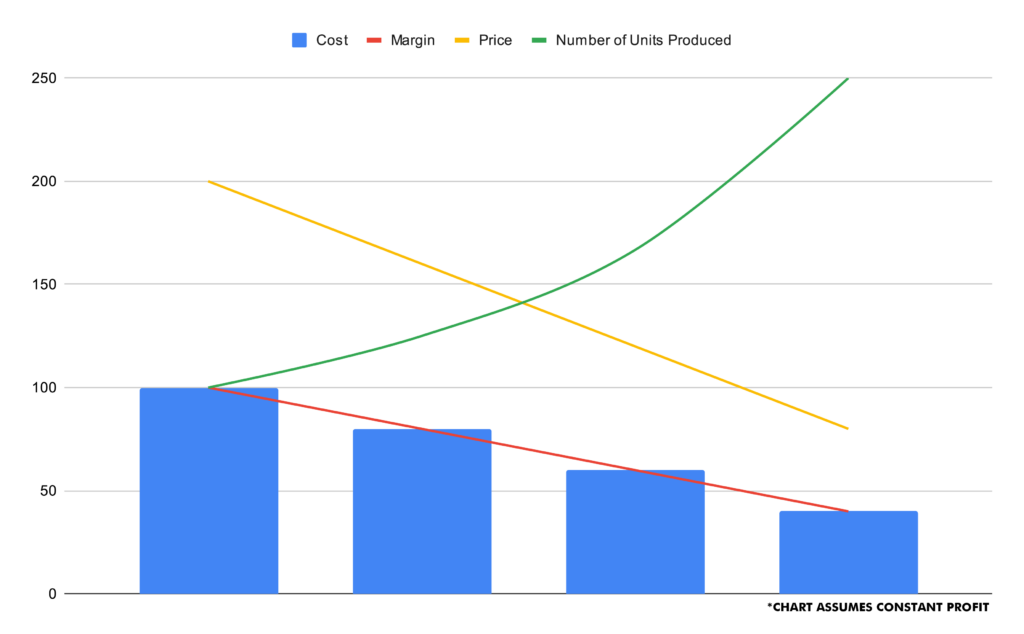

This chart shows how for profit levels to be maintained as technology advances, more units must be sold while workers are paid less.

Thus products are produced, but fewer and fewer people can purchase them. This value crisis is relative to production and accumulation rather than simply “making too much stuff.” The value of a product goes down, so the capitalist makes more of it to sell, ultimately at a lower price, due to the opportunity created for competition (or simply to head it off at the pass). However, the consumer purchasing power decreases quicker than the price (making $0 tends to do that).

So the capitalist has “overproduced” in that they produced “more” than anyone can buy, but not because they miscalculated and produced too much. It’s because they operated their business like a businessperson. It’s inherent.

Degrowth Advocates’ Usage

Degrowth argues for a reduction in global consumption and production (social metabolism). [source]

Note the literal frame “overproduction” exists in. Further, note that “excess consumption” is listed as a problem, however, is literally impossible in a situation of “overproduction” by Marx’s definition, where increased production decreases wages and employment.

Degrowth proponents advocate for a deliberate reduction in economic output (and consumption, sometimes masked as “energy production,” which they understood to be a product of demand and not a life-sustaining substrate). This, in their heads, “solves capitalism.” Somehow, as we produce less and distribute it “to everyone,” things magically improve.

The issue is this is merely a policy proposal and does nothing to address the fundamental flaw of capitalism (meaning we will retain what gives capitalism its very character). While distribution in the degrowth paradigm is “better,” it creates a situation of less availability rather than abundance (when taken to the extreme, as with Sri Lanka, it creates scarcity). This is why those of us taking the Marxist line wish to address the conflict appropriation creates, which is not simply about taking the product away from the rich and distributing it. All this does is maintain class lines even if not profit.

The fundamental flaw of appropriation relative to production that I described in the previous section creates opposing material relationships to the means of production: owners, who retain the product and therefore any possibility of profit, and their subordinates, who, at most, retain a wage. Addressing this means addressing ownership, something the imperial geopolitical entities funding degrowth advocates like Jason Hickel (read: the EU via its research council) absolutely refuse to do. Instead, they set up organizations and take money from finance capitalists who want them to promote degrowth.

These people are happy to use a term from Marx, whose program ultimately calls for growth and expansion of the productive forces to create abundance after resolving the fundamental flaw mentioned earlier. It becomes obvious why Marx’s analysis and the literal definition of the word “overproduction” need to be separated if Marxists actually want to pursue an abundance paradigm: because they seem to really like putting words in his mouth, and someone who is taking the word literally likely doesn’t know the difference.

When Marx’s concept of overproduction is inaccurately equated with degrowth perspectives, it distorts the understanding of Marx’s critique of capitalism. Degrowth fails to recognize (and/or intentionally obscures) the underlying systemic contradictions, power dynamics, and class struggle that Marx’s analysis encompasses.

Ultimately, degrowth advocates assert the problem is “too much production.” Marx asserts there is a crisis of devaluation that wouldn’t be a crisis at all if not due to the mechanics of capitalism.

Conclusion

By doing so, the layperson focuses on value, which sets a Marxist up to talk about everything with a pre-emptive understanding of what is being addressed. The core tension is between value production and its realization in capitalist economies.

It is important to note that “better” terminology alone can’t ensure a “better” understanding of anything. Clear explanations and contextualization should accompany it, providing a foundation for people to engage effectively. However, simply setting it up as a crisis of value can serve as a bridge, encouraging readers to delve deeper into the underlying systemic issues and the contradictions of capitalism. Also, the point isn’t to erase the original term or to mandatorily discuss it with a new term; it’s to explain/frame it more simply for people who do not already have an understanding.

Ultimately, the term itself doesn’t matter; it’s the concept.

I hope that one day, we live in a world of abundance, where this dynamic no longer affects our lives. We get there by understanding more of what exists and has existed rather than simply lobbying the ruling capitalist class to change their motives and give us more stuff. There is a dialectical class struggle that, when resolved, will give the people of the world the ability to live better.

Fighting distortions in that critique (intentional and accidental alike) puts us in a better position to advocate and take useful action.

Peter Coffin is a comedian, political commentator, and member of the Center for Political Innovation. The original version of this article was posted on June 17th, 2023 in the Substack blog “P on Stuff”, alongside other pieces available here.